The European Natural Gas Crisis – Our View

The Russian cut-off of natural gas to Europe creates two risks:

- Supply risk: Some countries are at risk of a shortage of supply. Each faces different policy options to overcome this challenge.

- Price risk: Even if supply continues, all countries face higher market prices. We have assessed several countries for the impact on their current account, government budgets, and inflation. There are Euro Area implications for interest rates.

The good news is that even though Russian flows have reduced substantially, a shortage appears increasingly unlikely this winter. Prices and patriotism have led households and firms to cut consumption more than expected. Gas storage levels are now practically full.

Supply Risk

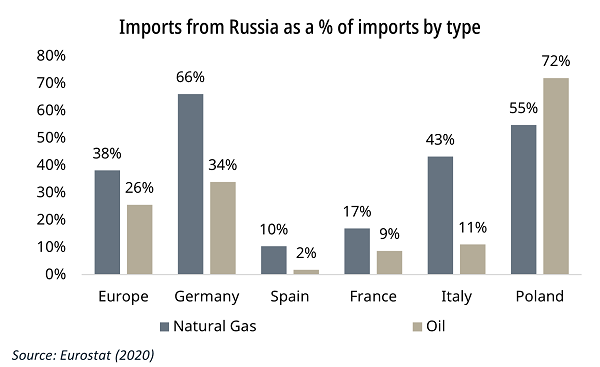

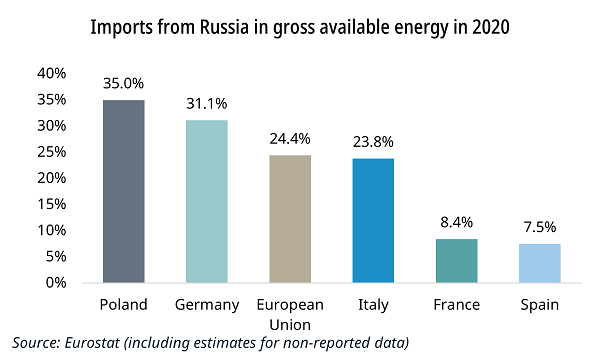

The reliance on Russian natural gas varies drastically by country:

- Germany and Italy stand out among the large European economies as having a large reliance on Russian gas.

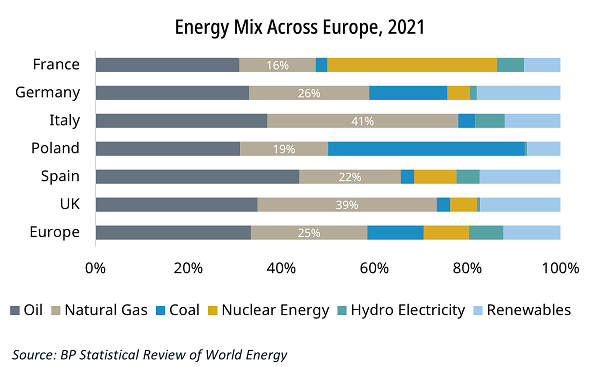

- France, by contrast, uses far more nuclear energy than its peers. This is because, after the 1973 oil shock, France embarked on the Messmer Plan to lessen reliance on oil and move further towards electrification based on nuclear power. In October, 26 of France’s 56 nuclear reactors were, however, offline.

- Finally, Spain uses some natural gas, but only 10% is imported from Russia. It has a large amount of spare LNG capacity.

Germany: Natural gas is the second largest source of energy in Germany, accounting for 26% of the country’s gross available energy. It imported 55% of this gas from Russia in 2021. Norway is the next largest supplier. Solid fossil fuels and nuclear have been in decline in Germany since 2013, with the share of renewables and natural gas increasing.

On paper, Germany has two key issues:

- LNG: Germany currently has no active LNG terminals, relying entirely on piped gas. Germany has moved quickly to charter five floating LNG import terminals, two of which will come online before the end of the year. The remaining three will be active by next winter.

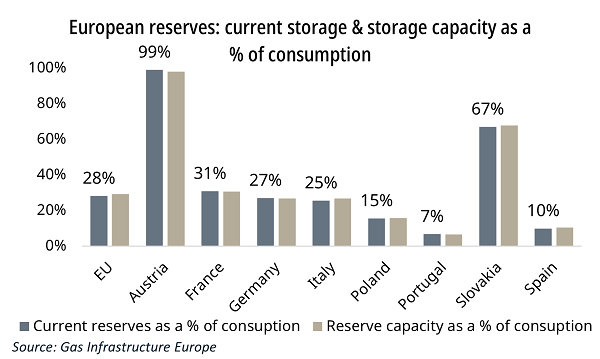

- Storage: Germany has a relatively low storage capacity. However, Germany’s neighbours have large reserves relative to their consumption, specifically Austria.

Italy: Italy has a high import dependency at 73.5%. In 2020, 41% of its gross available energy was from natural gas, and 43% of this gas was imported from Russia. On the face of it, this appears to put Italy in a worse position than Germany. However, Italy does have some advantages that partially compensate for this strong dependency.

- Storage: It has more storage relative to its consumption than Germany.

- Pipelines to North Africa: It has existing infrastructure that will enable it to switch to alternative sources of natural gas. A new deal with Algeria has already been signed to increase flows by roughly 40%.

- LNG: It already has three LNG terminals, and only 50% of capacity was used in 2021.

Despite the European natural gas crisis, it appears that Germany and Italy will make it through this winter without disruption. Much will depend on the weather, as a cold winter sends household gas consumption higher.

Price Risk

The European natural gas crisis has pushed prices on energy up across the board. There has been a fall in recent weeks, but the prices are still elevated. This will act on European economies through several channels.

PPI and CPI: In the short term, the industry will have to pay much higher energy prices, causing PPI first to increase, then CPI. Longer term, a switch to LNG will still be more expensive as the regasification process adds complexity and cost to the process of importing gas.

Current Account: The price effect worsens the current account of European countries in two ways:

- Net energy importers (most countries) will have to pay more for their fossil fuel imports.

- It will decrease the international competitiveness of European firms that pay these higher prices, which will act to decrease exports.

The UK is a prime example of a country that stands to lose out from these effects. It runs a significant current account deficit and is a net energy importer. It will have to raise interest rates substantially to attract foreign capital to finance the deficit. Otherwise, the currency will fall, and the deficit should move toward balance.

Interest rates: The ECB cannot print gas. It is facing inflation fueled by an energy shock that cannot be targeted by monetary policy. However, sticky and self-propelling inflation, which emerges on top of the energy shock, can be targeted.

This self-propelling inflation generally occurs when workers demand higher wages to compensate them for the higher cost of living, driving the price of goods and services higher. This can prompt further rounds of pay increases.

This has not taken place yet in the Euro Area, but it has begun in the US. Negotiated wages in the Euro Area only climbed 2.4% in Q2, while average annual hourly earnings increased 5.0% YoY in the USA in September. This fact has not been missed by policymakers. Philip Lane, ECB chief economist, noted in the minutes of their latest meeting that “In the United States, the pick-up in core inflation was closely matched by a pick-up in wage growth. This was not the case in the euro area, where there was a clear disconnect between the evolution of core inflation and that of negotiated wages”.

In our published work for clients, we detail how the European natural gas crisis will work to move these economic metrics. We have published thorough reports on the energy crisis in Spain, Italy, France, Germany, the UK, and the Republic of Ireland. To access these and other reports, please reach out to us here.

If you would like to access our work, Carraighill Research Access enables you to access these and other thematic and sectoral research through our secure online portal. It also gives you access to investment ideas across the banks, payments, fintech, asset management, and real estate sectors for European and select emerging markets. If you would like to speak to a partner or analyst on the topics raised in this piece, you can contact us here.