Has Political Pressure Resulted in UK Monetary Policy Failure?

The banking system data we cover from the UK brings into question the Bank of England’s ability to rein in inflation given pressures from the government to pass on higher rates to depositors. This short blog seeks to explain this, and why it is important for investment decisions in UK companies.

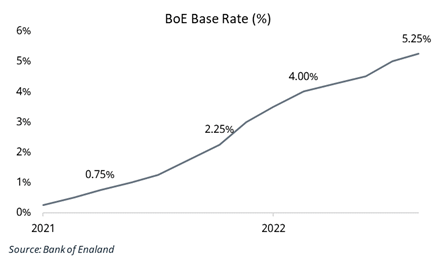

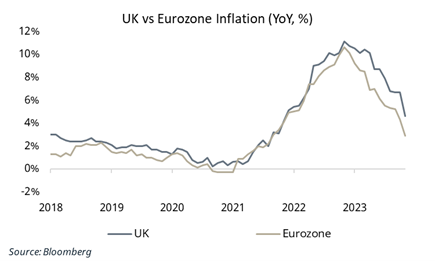

In June, the UK government put pressure on banks to pass higher rates on to savers. This increased households’ spending power amidst rising CPI and core inflation. Why?

Traditionally, the banking system has been used by central banks to control the money supply through higher rates. There are two ways that this occurs:

- Loan growth slows: This is happening in the UK, with private sector loan growth declining from 2.7% YoY in Q1 of this year to 0.4% in Q3.

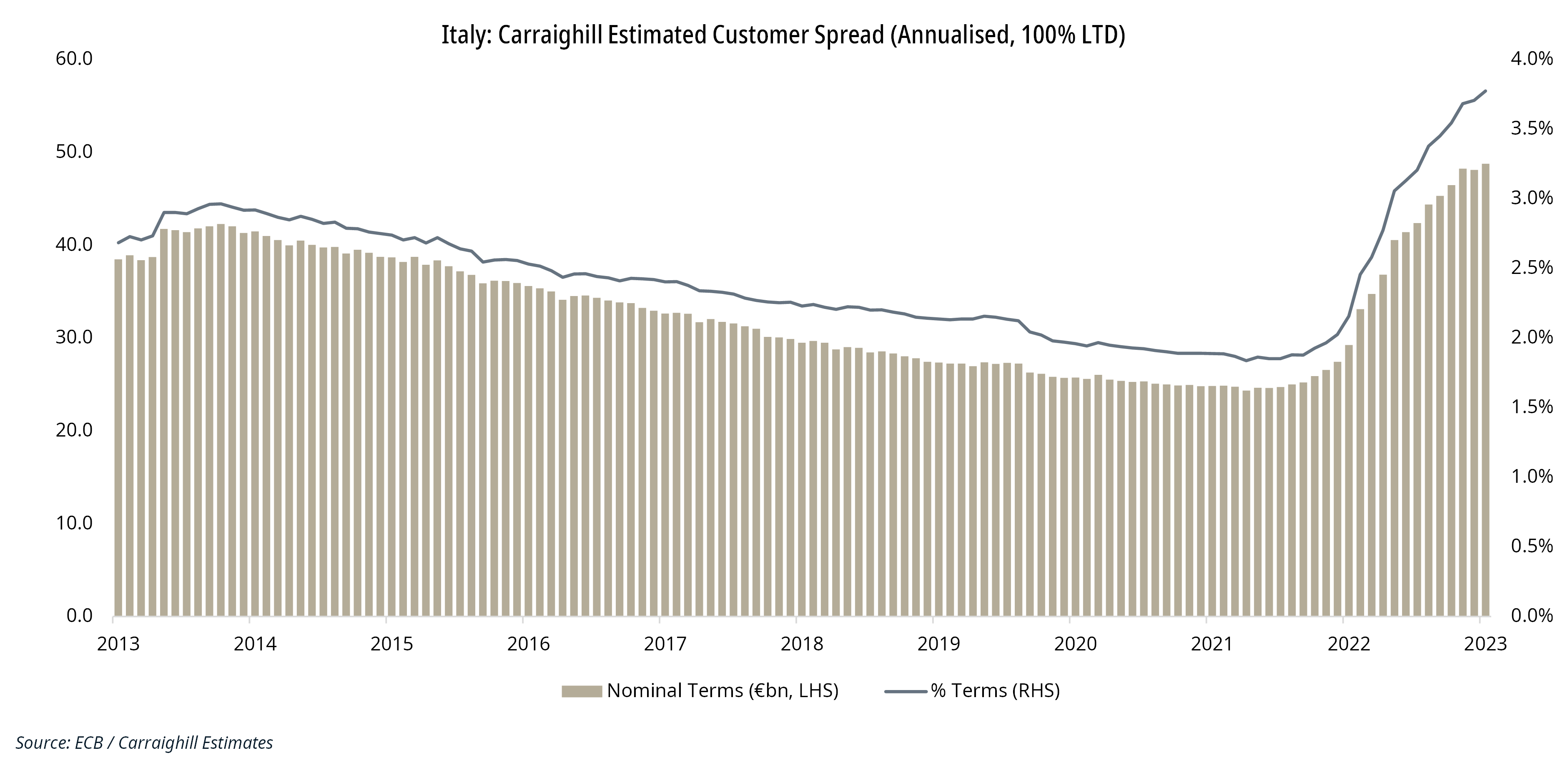

- Banks also traditionally transmit the CB’s policy to the private sector through a higher customer spread: This means interest rates charged on loans increase by more than those paid on deposits, lowering household income. The opposite is happening in the UK.

We note:

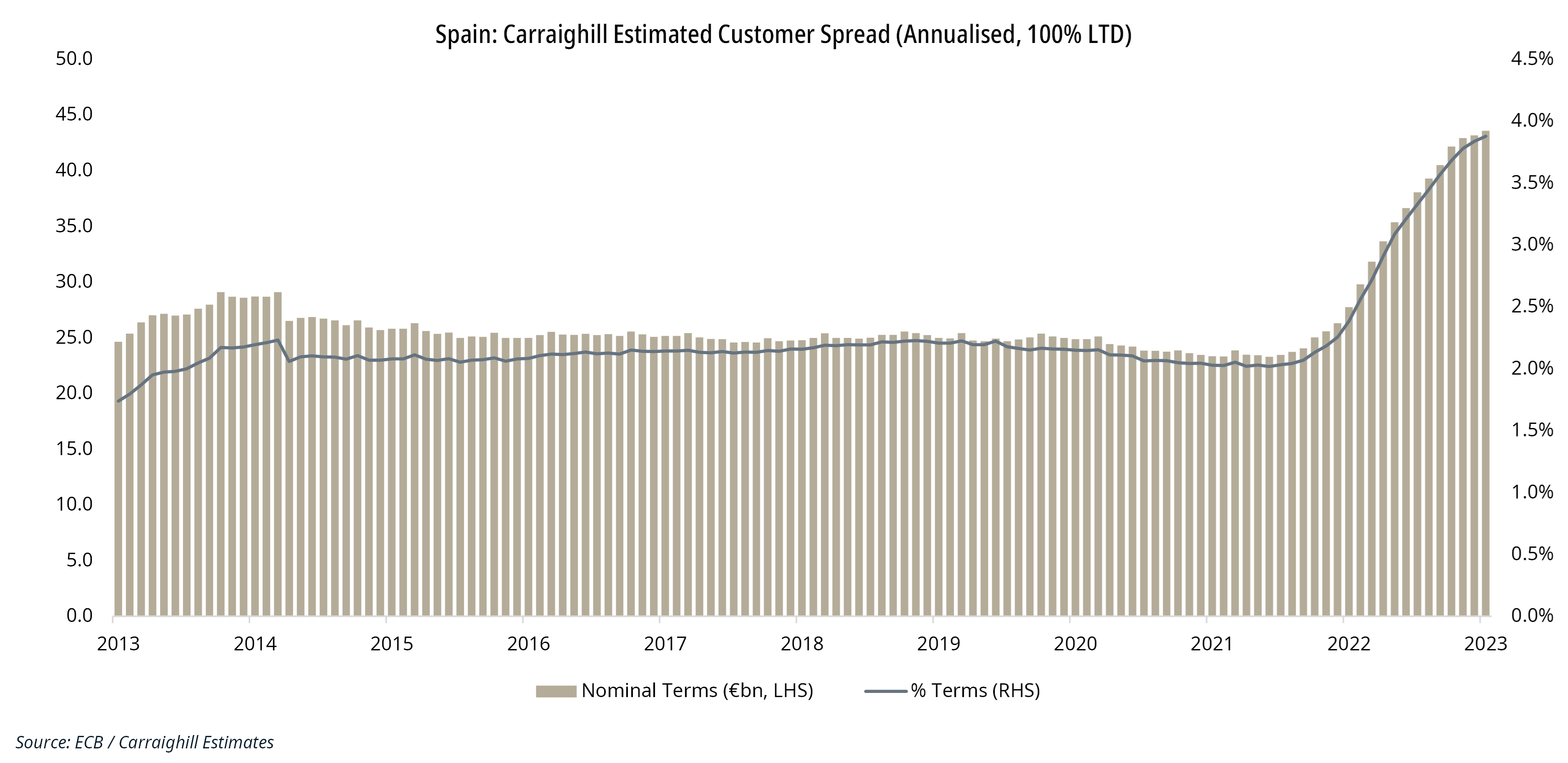

- The UK banks’ customer spread is being squeezed: The latest (September) figure was 1.89%, a 39bps drop when compared to the same month in the previous year. It was 240-250bps pre–pandemic. A low spread is disastrous for UK banks’ top lines. In contrast, the spreads in peripheral countries such as Italy and Spain have risen by c. 190bps and c. 180bps respectively since 2021.

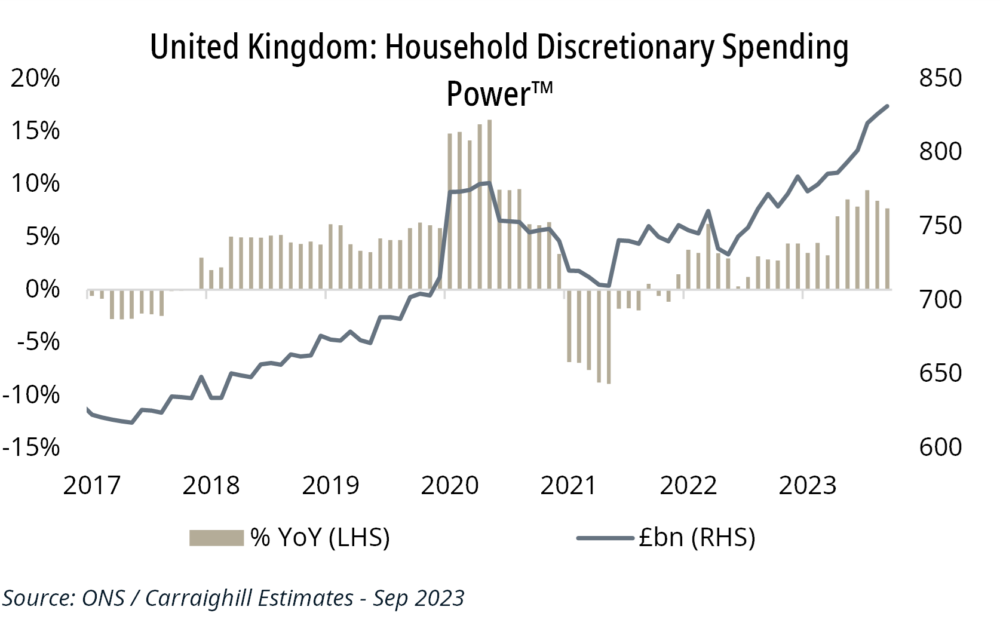

- Because of a tighter banking spread, the interest income received by UK households has grown by far more than their interest expense: In 2020, UK banks paid just £5.1bn in interest on deposits to households, at the same time taking in £37.8bn in loan interest. The September data shows an annualised rate of £42.3bn for interest paid on deposits (up c. 730%), whilst interest income from households has grown to £55.9bn (up c. 48%). This undermines the effectiveness of monetary policy as service inflation stays higher than it should normally be. Note: It is worth mentioning that the average household receiving this additional interest on their deposits is likely to be wealthier – which rewards the richer parts of society relative to the younger cohorts who wish, for example, to buy a house.

- At 45.7%, the UK has by far the highest deposit beta in Europe, dwarfing the likes of Spain (9.7%) and Ireland (8.4%). The deposit beta measures the proportion of an increase in the interest rate that is passed through to deposit holders. The UK’s figure of 45.7% implies that a 100bps increase in the bank rate would result in a 45.7bps increase in deposit rates. In June of this year, UK banks came under pressure to pay higher rates to savers, with the treasury committee describing the available rates on instant-access deposits as “measly”. Following this, the UK government began to directly compete with the banks, with the state-backed NS&I offering savers 6.2% on 1-year savings.

- Wage growth also remains strong, further supporting household disposable income: Household Discretionary Spending Power rose 7.7% YoY in September in nominal terms amidst 7.8% YoY growth in wages. This is above the rate of essential item inflation (6.8% YoY). This level of price increase is higher than G7 peers.

Has political pressure to provide higher wages and pay more on deposits contributed to a more difficult path of policy normalisation and kept rates higher for longer than otherwise may be the case?

We think so, but these are only some of the key factors to consider when one thinks about investing in UK companies.

If you would like to access our work, Carraighill Research Access enables you to access these and other thematic and sectoral research through our secure online portal. It also gives you access to investment ideas across the banks, payments, fintech, asset management, and real estate sectors for European and select emerging markets. If you would like to speak to a partner or analyst on the topics raised in this piece, you can contact us here.