Banks & The Yield Curve

What do banks do and how do they make money?

The simple answer to this question is that banks borrow short and lend long.

What does this mean? Essentially, banks take in short-term deposits and lend this money out as long-term loans to households, companies and the government. They do this because short-term interest rates are usually lower than long term interest rates; banks pocket the difference, and this amount is the net interest income (NII). This is the primary source of income for many banks.

What is the yield curve?

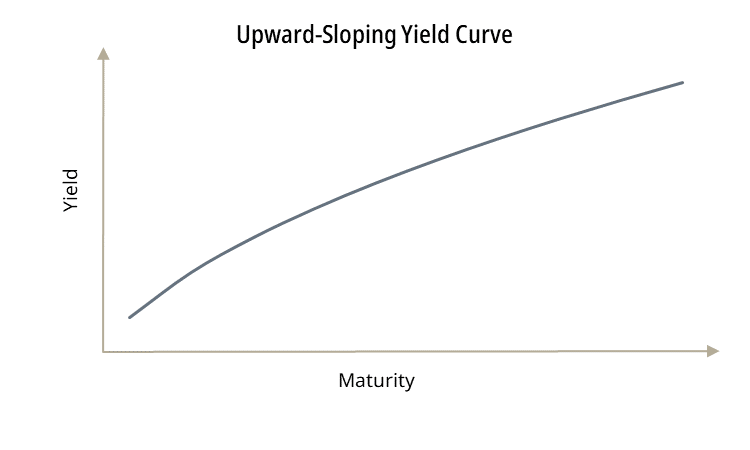

The yield curve represents the bond yields over different terms to maturity. Usually, the yield curve is upward-sloping, meaning that the yield on short term lending/ the cost of short-term financing is lower than in the long term. The elevated cost for longer term financing reflected in a normal yield curve represents the risks associated with potential changes in financial conditions over the course of the loan, for example inflation, higher central bank interest rates or changes in borrowers’ ability to pay back the loan over the long term.

For example, a lower interest rate would be expected on a 2-year fixed rate mortgage than on a 30-year fixed rate mortgage. This is understandable as the lender can have much more confidence in financial conditions over the next two years than they can over the next 30.

Do Central Banks set interest rates? No – the market determines the rate, although they do have some control over the very short term. So why does the yield curve matter?

Central banks only set very short-term interest rates. They have much less control over the cost of longer-term lending, which is set by banks and financial markets. Various factors determine the price of longer-term lending, including:

- Fiscal policy

- Investor expectations

- Economic Growth

The yield curve is important, because the price of mortgages and business loans, or the cost of borrowing for the government, will be determined by the expectations embedded in the yield curve and not simply the current central bank interest rate.

Why does this matter now?

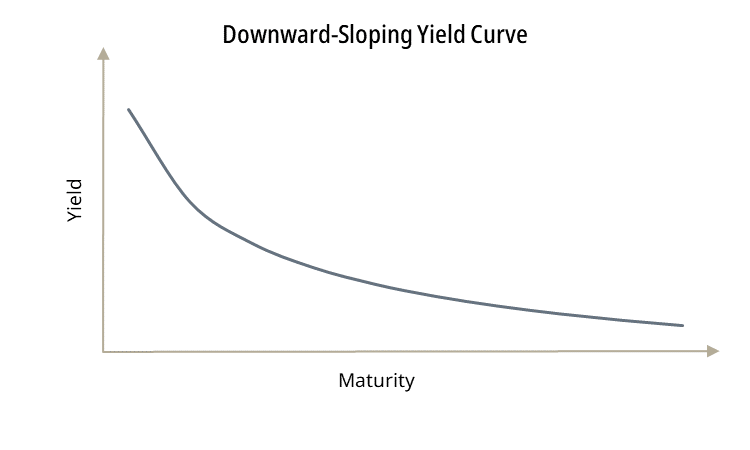

Since April 2022, we have had an inverted yield curve across most developed economies, including the key benchmark US Treasury yield curve. This means that short term bonds have been yielding more than long term bonds. However, in the last few days, we have seen the curve steepening and the current inversion coming to an end.

Back to Banks:

A steep yield curve is usually positive for banks because as we have already learned, they want to borrow short and lend long.

However, since the yield curve inverted, the SX7E European banks index has performed reasonably well with a c. 52% gain.

How has this happened? During this period there has been very limited new loan growth for both European and US banks. As a result, banks have been able to:

- Place their excess deposits at the central bank and receive the risk-free central bank yield, which has risen considerably during this period (borrowing short and lending short), and

- Return excess capital to investors through share buybacks and dividends.

Looking forward

Following the strong share price performance of European Banks over the last few years, a mistaken narrative has emerged that when central bank interest rates rise, bank earnings also rise and vice versa.

We believe this is far too simplistic.

While a range of factors influence the share price performance of banks, the transition to an upward sloping yield curve is one factor that should be a positive for bank earnings, particularly as it allows them to implement their most basic strategy of borrowing short and lending long, increasing NII and profitability.

If you would like to access more information and in-depth analysis on these topics, Carraighill Research Access enables you to access these and other thematic and sectoral research through our secure online portal. It also gives you access to stock investment ideas across the banks, payments, fintech, asset management, and real estate sectors for Europe, the UK, Scandinavia and select emerging markets (Brazil, Mexico). If you would like to speak to a partner or analyst on the topics raised in this piece, please contact eoin@carraighill.com.